How to Deal With Difficult Concepts

Let's examine the nature of difficult to understand concepts so that we can change our approach and “get them faster”.

Hi Friends 👋 ,

This is a part one (I), of a two-part (II) series about dealing with difficult concepts or tasks. I had to split the topic into two articles because the complexity of the subject an the need to do more extensive research. Let’s jump in.

Learning can vary from being trivially easy to impossibly hard. Similarly, some concepts can be easy to get, while others… impossible to grasp. The same is true about tasks. In this piece, I want to look at the concepts & tasks that (for the particular reasons that we will get to soon) are hard to understand and deal with.

We will look at the hard concepts.

The difficult ones.

The black sheep of the concept family.

The Malfoys’ of the tasks.

Let’s look at the concepts first. I’m sure you have met ‘these’ concepts in the past. You know… the concepts that leave us to growl and curse angrily, the concepts that frustrate us, those pesky ones that make us regret our life choices, and curse our curiosity. Yep, we will deal with these too.

The good news is that it’s not only doom & gloom.

When we look at the available research on learning and understanding – it appears that we can actually surface sensible strategies that will help us to understand these difficult concepts – in business, product, and consulting work.

But before we start answering the question of why some concepts are so hard to understand – we should make a distincition between a concept and a task.

There's a subtle difference between these two.

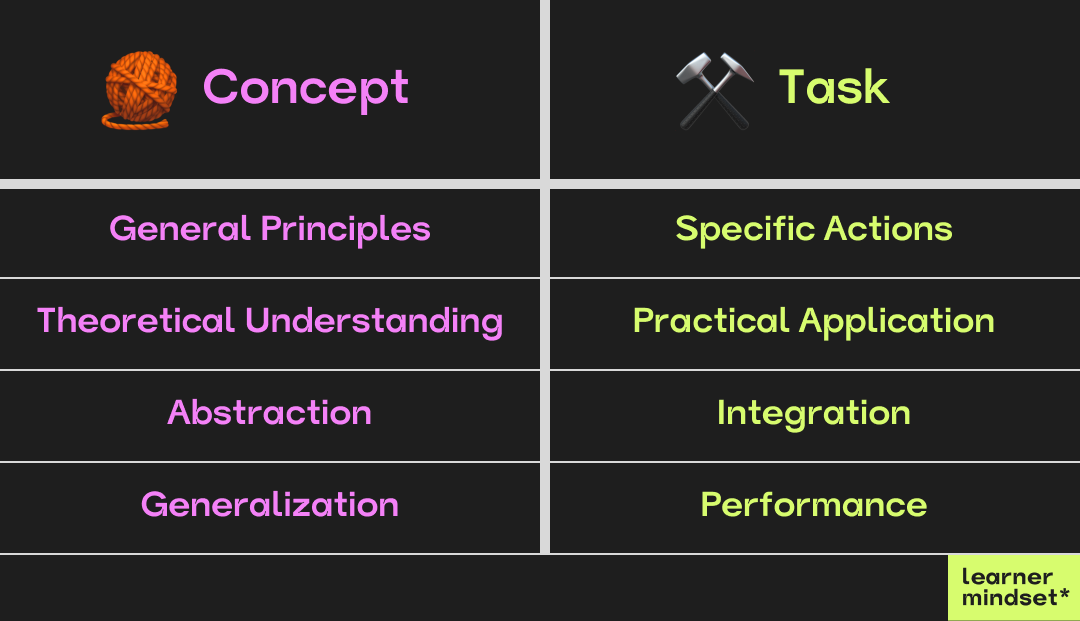

A concept tends to refer to an abstract idea or a mental construct that needs to be understood. Concepts are typically general principles that can apply to many different scenarios. For instance, "innovation" or "equity" are concepts that can manifest in various forms across different business situations.

A task, on the other hand, is more concrete and action-oriented. It involves applying one or more concepts to complete a specific activity. For example, creating a marketing plan, conducting a financial audit, or implementing a new business strategy are tasks that would utilize various underlying concepts.

The naming differences do matter when discussing learning difficulties because:

Learning a concept often means understanding a theory or principle which can be abstract and not immediately linked to a tangible action.

Learning a task usually means understanding how to apply concepts in specific actions to achieve certain goals.

While both concepts and tasks can present learning difficulties, the nature of the challenge is different. Learning a concept might involve grappling with abstract ideas, while learning a task might involve integrating several concepts simultaneously into real-world practice.

So, within the context of a learning difficulty, concepts and tasks should not be used interchangeably without considering these nuances. The difficulty in understanding a concept lies in the abstraction and generalization, while the difficulty in performing a task may involve the application and performance of that concept in a specific context.

I promise all of this will get clearer with examples as we dive deeper into the subject.

There’s nothing wrong with you

Ok let’s get one thing out of the way swifltly. When faced with difficulty of understanding a particular thought, idea, or process, some of us tend to blame ourselves for “not measuring up”. I’m stupid, I’m not intelligent enough, my mind is too scattered to focus, it’s not for me, I’m this… or I’m that… – these are the things we say to ourselves to cope with the situation.

This is bullshit. You, my friend, are not to blame for this – the concepts and tasks are. It’s the very nature of some concepts and ideas that makes them particularly hard to grasp and deal with. So don’t put yourself down anymore, and relieved, join this exploration with an open mind.

The five criteria

How hard something is to understand is a function of five criteria:

Amount of information

Complexity of the concept

Thought patterns

Prior knowledge

Quality of explanation

Let’s explore these five criteria in more detail now.

Amount of information

This one is pretty straightforward. Basically, the more information-dense a concept or subject is, the longer on average it takes to grasp it. For example, while a company policy manual might be very thick, detailing various rules and scenarios, each policy is often a discrete piece of information. A reader could potentially review each policy independently to understand it.

But it’s not the only criterion – studies have shown that two tasks may appear to have roughly similar amounts of information but differ enormously in the effort required to achieve mastery.1 To explain what happens there, we should turn to the second criteria, which is the complexity of concept.

Complexity of the concept

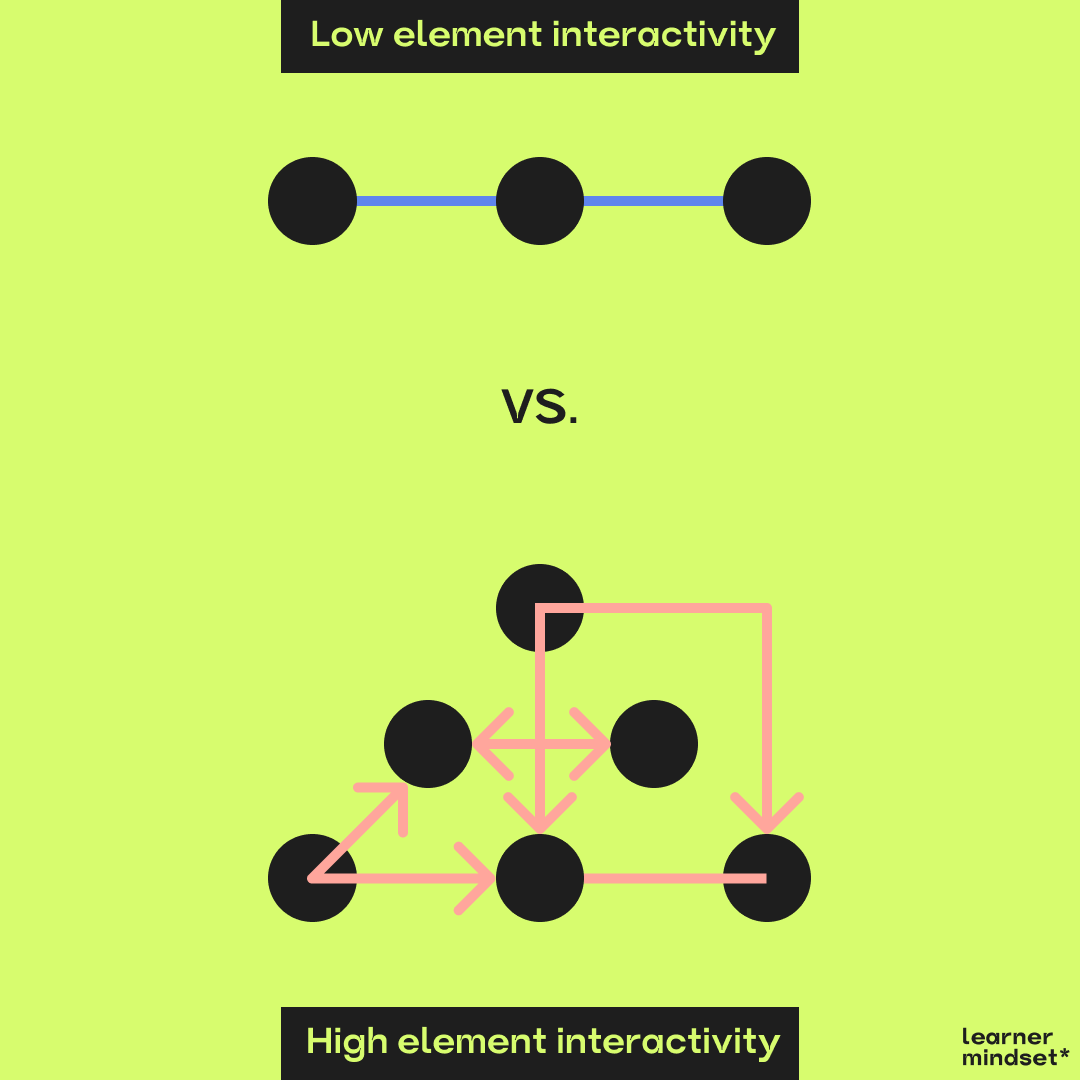

The more complex the concept is, the harder it’s to learn it.2 Some concepts are naturally more complex than others. What do we mean by that? Well, it relates to the situation in which a given concept is made up with smaller elements. Notice what happens as a result of this construct. Now you have a) elements, and b) interactions between the elements that make up the whole concept. The total amount of elements and interactions make a given concept simple or complex.

In addition, all concepts will have so-called low or high “element interactivity”. Element interactivity refers to the extent to which elements within the material being learned interact with each other. Elements are considered 'interacting' when the understanding of one element depends on the understanding of another. High element interactivity implies that to learn something effectively, one must understand how various elements influence one another; low element interactivity means that elements can be learned in isolation without much consideration of the others.

When dealing with difficult concepts and tasks, it's often the case that we can rather easily understand the theory, but the practical application is what gets us. This is especially important and relevant in business context.

Let’s have two examples now, one related to unit cost analysis, and the other to implementing innovation.

Grasping the basic idea of “unit cost”, which is simply the cost incurred to produce, store, or ship one unit of a product, involves low element interactivity. It's a straightforward calculation: divide the total cost by the number of units. Yet, applying unit cost analysis for business decision-making is a whole of a different ball game. Why? Because using unit cost analysis in real-world business scenarios involves high element interactivity. Decisions based on unit cost analysis must consider production efficiency, economies of scale, pricing strategies, and market conditions.

Now onto the innovation example. Innovation as a concept can be understood with low element interactivity, as it is basically the process of translating an idea or invention into a good or service that creates value. Yet, executing innovation within a company involves high element interactivity. Just think about all the requirements that need to be met for it to emerge. It requires for example integrating market research, design thinking, project management, corporate strategy, and often, cultural change.

Thought patterns

This one is interesting. And it’s related to our beliefs and maladaptive ways of thinking. Maladaptive ways of thinking are thought patterns that inhibit learning, problem-solving, and decision-making processes. These patterns often involve cognitive biases or simplifications that distort your perception and understanding of reality.3 In business context, maladaptive thinking can manifest as a reliance on overly simplistic models of understanding, leading to misconceptions and a failure to grasp the nuanced interactivity between different components of a subject.

A common form of maladaptive thinking is the aforementioned "reductive bias," where learners overly simplify complex systems or concepts. For instance, in a business setting, this could involve a manager attributing the success or failure of a product solely to one factor, such as marketing strategy, while ignoring other critical aspects like market trends, product quality, or customer service.

Maladaptive thought patterns are characterized by resistance to new information, particularly when it contradicts existing beliefs or knowledge frameworks. In business, product management or product design, this resistance can hinder your ability to adapt to novel scenarios that require flexible thinking and a willingness to update your mental models.

The next time you are faced with a concept or task that’s difficult to understand, stop and zoom out for a second. Run a quick check, and confirm you are not making it harder for yourself just because you are unconsciously protecting some of your beliefs from change.

Prior knowledge

Prior knowledge plays a critical role in understanding complex concepts or tasks, serving both as a foundation to build upon and as a filter through which new information is interpreted.

When you encounter a new concept, you instinctively try to connect it with what you already know, aligning the unfamiliar with the familiar to make sense of it.

But there’s a catch. This cognitive anchoring can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, a solid base of relevant prior knowledge can make it easier to absorb and understand nuanced information, essentially providing a mental scaffolding from which to hang new ideas. For instance, a seasoned financial analyst is likely to grasp advanced investment strategies more swiftly than a novice because they can draw upon their deep understanding of financial markets.

On the other hand, the learner's existing knowledge base could be riddled with inaccuracies or misconceptions – referred to as 'misconceptions' in education research. This means that new concepts that contrast with these preconceived notions can be particularly challenging to internalize (fixed belief!). This kind of prior knowledge can cause learners to misinterpret or outright dismiss new information that doesn’t quite fit into their established mental model (see the relationship with Thought Patterns?). For example, in a business context, if a manager has misconceived ideas about consumer behavior, they may struggle to accept emerging trends that go against their ingrained beliefs, possibly leading to misinformed decision-making.

To summarize – building upon your prior knowledge is essential in facilitating the mastery of complex concepts or tasks. If you lack prior knowledge in certain areas, it seems clear that it will be more difficult for you to grasp certain concepts. Sorry, but that’s the reality. Yet, worry not, because this too I believe can be resolved by the right methods and approaches. We will get to them later.

Quality of explanation

Finally, you might have a challenge understanding a concept because it’s poorly explained to you. A well-crafted explanation acts as a guiding light that can lead us through the dense forest of new and difficult ideas. It breaks down the concept into bite-sized pieces, clarifies relationships between different elements, and anticipates questions and misconceptions that might arise. Good explanations often use analogies, relatable examples, and clear, jargon-free language to make abstract concepts more concrete and easier to visualize. For instance, describing the internet as a "series of tubes" simplifies a complex network of protocols and devices into something tangible, helping someone new to computer networking grasp its basic structure.

Conversely, a poor explanation can leave us lost and adrift. It may skip steps, assume prior knowledge we don't have, or fail to connect new information to concepts we already understand. This leaves gaps in our cognitive map of the subject matter, making it much harder to reach a clear understanding. What’s more, if an explanation introduces its own inaccuracies or biases, it can foster those stubborn misconceptions that are so difficult to unlearn later on. In the business world, imagine trying to understand market fluctuations with an explanation that ignores economic fundamentals and focuses only on investor sentiment. Even though you will feel you understand some of the dynamics there — you will still have blind spots. Such a narrow view could lead to a shaky understanding of market dynamics, making effective investment decisions much trickier.

The “quality of explanation” is the last of five criteria influencing the difficulty of concepts. Armed with this knowledge, we can progress to the second part of the article.

The next article in this 2-part series will cover the 3 Effective Strategies For Understanding Difficult Concepts. Stay tuned!

“Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design”, John Sweller, University of NSW, Australia.

“The Simplicity Principle in Human Concept Learning”, Jacob Feldman, Department of Psychology and Center for Cognitive Science, Rutgers University, New Jersey.

“Learners' (mis)understanding of important and difficult concepts: a challenge to smart machines in education”, Paul J. Feltovich, Richard Lorne Coulson, Rand Spiro.